Article published in the journal of the French Harp Association (AIH), n°45 AH/2007

Revised and expanded in March 2020

EN | FR

The Pleyel Harps

II. The Chromatic Harp

Curiously, it was again Belgian harpists (like Dizi before them) who had a defining role to play. Félix Godefroid [4], and Alphonse Hasselmans [5], waited for Wolff's successor, before suggesting to Gustave Lyon in August 1894, that he resume making double-action Pleyel harps.

Despite the stature of the elderly Godefroid, 76, Gustave Lyon declined the proposal. He could not take up an instrument whose principle had been condemned to failure by his father-in-law forty years earlier. On the other hand, Lyon immediately started thinking about a simple and affordable chromatic system, with a view to a reliable and accessible instrument. Two years later at the end of 1896, the very first Pleyel chromatic harps, with crossed strings, came out.

This system was inspired by certain antique harps with several rows of strings. It had already been considered in 1843, but never implemented, by another great French piano maker, Henri Pape [6].

In the end, even though he closely followed all its developments, Félix Godefroid did not really have time to appreciate this new Pleyel harp: he died in 1897. As for Hasselmans, he never saw even the slightest future for this new instrument.

In the first instance, the chromatic harp principle looks more accessible than the double-action mechanism. As on the keyboard, the notes tuned in naturals are white, and the altered notes are black. Only the C strings were red, keeping the same visual reference as on a pedal harp.

All the strings were attached to the famous Alibert pegs, which were abandoned on the piano. To avoid any confusion, the F strings were made white, instead of their usual blue or black.

These two types of strings, white and black, i.e. natural and sharp, were not arranged on a single axis as on a pedal harp. Instead, they were strung on two X-planes, crossing each other in the first third of the string length. The white strings were stretched from the left hand bridge to the right hand side of the console, and vice versa for the black strings. This arrangement offered a certain comfort for the left hand in the low register and to the right hand in the high register - or at least, more comfort than the opposite stringing would have done.

The two planes did not have the same number of strings. Like the piano, the white strings had the full diatonic scale[1] , and the black strings only 5 notes: C#, D#, F#, G#, and A#. The full range of the Pleyel harp corresponded to that of a 46-string harp, from low D (D44) to high G (G00). This made for a total of 78 strings: 46 white strings, and 32 additional quarter tones.

It should be remembered that at this time, the range of all 46-string harps - especially Erard harps - was not from D to G, but from low C to high F. It was not until 1886, when the London factory closed, that Erard harps were equipped with the 47th high string, the G00.

l’élégante courbure du croisement des cordes

The spacing of the white strings was completely homogeneous. As on a pedal harp, it remained identical between the diatonic tones and semitones. The space between the strings was relatively small at the cross-over, and the position of the strings had to be very precisely adjusted. Each black string had to fit exactly between the two white strings, in order to prevent it from slamming against one of them. Also the bridge pins of the white strings were fixed, and those of the black strings were adjusted horizontally. These shifted the string to the left or to the right, according to which adjustment was needed.

The 78 strings required a new designation. Unlike the Erard system, the numbering no longer ran from high to low (E1, D2, C3...), but began in the low register, as with the piano.

Curiously, this numbering did not start from No. 1, but from 15 for the first note, the low D (D15, D#16, E17, etc). In reality, Gustave Lyon relied on the theory that the lowest sound audible to the ear is the 32-foot C [7], that is, the sound just below the lowest pitch of the piano.

This lowest sound, the original sound, was numbered 1, and chromatically determined all the others: C1, C#2, D3, etc. Also, the low D of the chromatic harp corresponded to the 15th sound on this scale, and the highest G to G92.

It is still quite surprising that Gustave Lyon chose this somewhat abstract numbering, instead of the usual piano system. And if he liked this numbering, logically he could have numbered his piano keys in the same way. Perhaps he had simply been considering enlarging the register of his harp later, by adding even lower strings. He could then have kept the same numbering: a new system of string numbers would have been chaotic for many harpists and string dealers. But in any case, no Pleyel harp goes beyond D15.

The most beautiful soundboard strip models are finely carved in the manner of an inverted rack. Under each string, the corresponding number is engraved, thus facilitating replacement in the event of breakage. The harp is strung with gut, and the low strings are wire up to and including Bb36 (which corresponds to Bb32, the 5th octave of the pedal harp). The Erard harp, on the other hand, is designed for strings only up to the 6th octave E, the gut starting at the F.

On the pedal harp, the strings are only attached to the neck on the left hand side. This causes a significant imbalance. It is not uncommon nowadays to find Erard harps with a warped neck, because the weight of the strings all pull on one side. Over time, the neck can lose its position parallel to the axis of the strings, which then risk escaping from the axis of the discs.

On the Pleyel harp, however, the arrangement of the strings on each side of the neck keeps a much better balance. The white strings - more numerous - pull a little more than that of the black strings, but the tension is nevertheless generally better distributed than on Erard harps.

It is precisely this asymmetry that Dodd and Dizi had planned to abolish in their harp with central mechanics; so did Henri Pape, with his project for a cross-strung harp. If it had been built, Pape’s harp would not have dissociated the white strings from the black ones, as on the piano. Instead, it would have had two completely equal string planes. All the notes should have followed one another in semitones. Each plane would have been tuned in whole tones, and the scale by tone would have stayed in a mode limited to a single transposition. One plane would have played C, D, E, F#, G#, and A#, and the other, C#, D#, F, G, A, B (or six strings per octave on each side). The idea was ingenious, but it is easy to imagine the difficulties it would have posed for harpists, who would have had to juggle between the two scales in tones.

Gustave Lyon was certainly being honest when, anticipating possible accusations of plagiarism, he said he had not heard of the work Pape had begun on a chromatic cross-strung harp. Only by applying for a patent in Germany and America would he have become aware of the very different patent filed by Pape fifty years earlier. In the same vein, Lyon does not in any way attribute the idea of cross-stringing to himself, and instead cites a 15th century Scottish harp exhibited in a South Kensington Museum.

Symmetrical or not, the string tension remains much higher than that of a 47-string harp. To support the pull of its 78 strings, of well over three tons, the structure of the Pleyel harp had to be much more robust. As early as 1894, the first chromatic harp prototypes were designed with strength in mind.

The column was no longer a simple wooden assembly, but a hollow steel cylinder, thus offering much greater resistance. A wooden veneer, of a thickness depending on the model, covered this cylinder for aesthetic reasons. String calibres and lengths were recalculated to be used at their breaking point, for this is where they also sound best . Gustave Lyon then developed a rather complex and ingenious machine to measure the pulling force of the strings. Using it, he completed his first harp in just one year, based entirely on scientific calculations.

In August 1895, he tested this harp with the very humid climate of Villiers-sur-Mer, Calvados - probably in Félix Godefroid’s house in the country [8]. Contrary to Lyon’s predictions, the strings could not stay in tune, and kept breaking. The problem however did not come from the strings, since they were perfectly adjusted, nor from the humidity. The harp itself was the problem: Gustave Lyon measured that its frame could stretch up to 3mm, thus exceeding the breaking point limit

To get to the heart of the matter, he decided to replace the usual wooden necks with new ones made of metal: his father-in-law's famous Pleyel Steel. Stable and resistant, it was already in use on all pianos (these days, in the form of an aluminium alloy). Less than a year later, in April 1896, Lyon conducted the Villiers test again, but this time with two further case studies: a small Pleyel harp from 1840, and a Gothic-style Erard. The strings of the three harps were of course bought at the same time, from the same manufacturer, and put on the harps on the same day. The first evening in Villiers-sur-Mer proved to be particularly ideal for this kind of test, since a furious storm was raging in the region. The experiment went well: the following day, no string broke on the metal chromatic harp, whereas 14 had gone on the Gothic, and 15 on the older Pleyel. From then on, the Pleyel chromatic harp was deemed a success, and was quickly launched.

From this point, all Pleyel necks on all harp models retained this very particular form, much more for scientific than aesthetic reasons.

To ensure the same angle between the white and black strings, the strings needed to move away from each other at their attachments (bridge pins and soundboard strip) as their length increased. The neck was therefore not perfectly flat, as on a pedal harp, but gradually widened on each side, where the tuning pegs and bridge pins were attached. The neck thus thickened towards the bass, while maintaining its general curvature.

Similarly, the soundboard strips were not parallel, but diverged towards the lower register. To keep a correct crossing height, a little lower than halfway up the strings, the neck had to be a little wider than the distance between the soundboard strips. This gives the harp a surprising aspect, appearing almost wider than it is high.

The new metal neck, hollower and more robust [9], allowed a small kind of chromatic (!) xylophone to be fixed inside it. It served as a tuning fork for the harpist, allowing them to tune all the octaves according to these reference pitches. The 12 chromatic blades, scientifically tuned, were arranged perpendicular to the neck, and a mechanical system allowed small hammers to be operated from a key on the neck’s outside, in the manner of a celesta. The manufacture of this mechanism was in fact subcontracted to the Mustel firm, a famous celesta manufacturer. Initially, a thin cloth stretched under the neck concealed the mechanism. For these harp models, the Pleyel ledgers note "aluminium, partition, sans volets ". "Aluminium" probably refers to the neck, and “sans volets” (“without flaps”) to the reinforcement mechanism (very quickly abandoned on the chromatic harp). "Partition" does not refer to a music score as it normally does in French, but is part of piano tuner vocabulary. The piano tuner “partitions” his keyboard first by defining a section of about an octave, which is the principle of this little celesta. This partition was tuned to A 435 Hz, the pitch in use at the time.

The “partition” (diapason) inside the neck

Above the row of sharps pegs, the five sharps tuning knobs

the string springs

The Pleyel harp had to deal with the enormous tension from 78 strings pulling not only on the neck, but also on the soundboard. Gustave Lyon therefore conceived the idea of fixing the strings not directly against the soundboard, but to a piece of cast iron inside the sound body. However, this made the length of the strings behind the soundboard too short. This made them too stiff, which in turn effectively blocked and jammed the soundboard. Lyon therefore released the soundboard by attaching his strings not directly to the piece of iron, but to small springs of carefully calculated diameter and resistance.

The soundboard now functioned very differently to that of a diatonic harp. If the strings had been attached directly, the board would have had to have been much stronger, and therefore thicker and less sonorous. The system of metal and springs allowed the board to be thinner and more flexible, which is important for sound quality. The springs were therefore a great success in this regard.

The iron string base was thus attached at both ends of the harp’s sound body, and passed between the soundboard strips. The usual place for the sound holes now occupied by the iron base, they were doubled and offset to the (nearby) side, so that the strings could be attached. Before arriving at this arrangement, Gustave Lyon had placed these openings completely on the edges of the body, judging the usual central position "irrational in the old harps, since the dresses or the upper body of the performers covered them up completely".» [10].

In this model, the fittings protruded on both sides of the body, at the bottom and top. At the bottom, the column simply rested on it, held in place by the tension of the strings. At the top, the neck was bolted to the body, and the column fitted into the neck. A few decorations, always in cast iron, adorned the structure, lest the harp should look more like a machine than a musical instrument.

Basically, it is not wrong to compare this harp to the principle of the metal frame of the piano, since all the key parts of the structure are made of steel, whether they are bolted, compressed, or nested. The only parts still made of wood are the body, the base, the table, and the plating of the column.

wooden roulette wheel, inside the claws.

The major disadvantage of the harp remained its considerable weight: 60 kg. Gustave Lyon wondered “how such a heavy instrument could be handled by women’s graceful and charming hands.” [11]. To make it easier to move around, he installed small wheels at the front, under the clawed feet: tilt the harp slightly forward, and it can be rolled. These very practical wheels would also be put on every chromatic harps, and, since then, on some modern harps. Incidentally, it is amusing to find the same front legs used, shaped like lions’ claws, as on the older Pleyel pedal harps. These feet, rather out of proportion on the earlier instruments, seemed to have found a harp to suit them.

It may also be because of the excessive weight that the string bed would later be reduced to just 22 bass wires. The soundboard was then specially redesigned to support the weight of the 56 gut strings.

The body then regained the five sound holes that a pedal harp has, as opposed to six for the previous metal string base. The holes were only doubled in the bass register, so that the strings could be attached on either side of the string base.

The string base was fixed directly to the body, which explains the presence of a metal part in the form of a handle above the two lower sound holes. Like the previous version, it bends to rest under the column, thus reinforcing the anchoring system to handle the very strong string tension.

Pleyel chromatic harp #213, 1900. Cast iron neck, string base between the sound holes all along the body.

Pleyel chromatic harp #598, 1908. Cast iron neck, base only for bass wires.

Several woods were available: mainly maple and satinwood, but also sometimes mahogany, rosewood, lemon, Hungarian ash, walnut, or ezigo. The metal necks were gilded and varnished.

**

Finally, shortly before the 1910s, the chromatic harp gradually abandoned its metal neck in favour of a wooden one. This also saw the departure of the small celesta inside the neck. It was probably the excessive weight that persuaded Gustave Lyon to return to the harp with a wooden neck. This weighed 39 kg, closer to the approx. 30 kg of an Erard harp. Perhaps it was also due to harpists' prejudices about the acoustic qualities of metal - as pianists reacted, when faced with Auguste Wolff's Pleyel Steel pianos.

A new model was created, very ornate, in the Gothic Notre Dame de Paris style. It was gilded and abundantly sculpted at the shoulder. As Pleyel’s Gothic head looks, to modern eyes, much coarser than that of the Erard, it is not impossible to imagine that Pleyel was competing via the head design.

Pleyel gothic

Erard gothic

empire style, wooden neck

Another model with a wooden neck, this time in the Empire style, went back to the decoration of the metal necks. It has an elegant Corinthian column, finely carved and gilded with gold leaf. On this column, the base and the head with a leaf motif are slightly larger than on the version with the metal neck.

As with pianos, some harps were customised, for example in a Louis XVI style, or with thistle or even swan ornaments. However, their production was relatively sporadic.

empire style project

rich swan style

sober swan style

style Louis XVI

The Gothic and Empire models were not manufactured for very long, and were quickly replaced by a more sober style, called “style moderne” in the Pleyel ledgers. Discrete decorations replaced the gilding, as on the Erard twisted Empire style harp, a recent model at the time.

Pleyel empire style #605, 1908

Erard twisted empire style, 1912

It was probably this modern model that became the most widespread - no other model followed. It became more and more popular, and quickly replaced all the others: including, of course, those with the old metal necks. It was also brought out in a very elegant maple version.

***

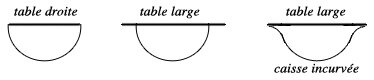

Necessarily larger than a harp with a single row of strings, the soundboards of the Pleyel prototypes were nevertheless straight, in the manner of the older Pleyel pedal harps..

They were subsequently expanded, much like the American extended soundboards. In 1895, the American firm Lyon & Healy [12] had filed the patent for the extended soundboard, as used on all modern concert harps (hence the expression “American soundboard”). Whether Gustave Lyon knew of the existence of this new harp on the other side of the Atlantic is uncertain. Later, Albert Blondel, director of Erard, would not entertain the idea of these soundboards on his harps.

The presence of two rows of soundboard strips required more width than on a harp with a single row of strings, especially in the bass because of the string spacing. The curvature was not as pronounced as on extended soundboards. Salvi now offered two harp models, the Arion and the Orchestra Ex, whose soundboards were somewhat reminiscent of chromatic harps. Of course, the wood grain of the Pleyel soundboards was always arranged horizontally to run across the width of the harp. The most richly-crafted ones are covered with a particularly elegant, fine veneer, often burr walnut or maple, as on older Pleyel pedal soundboards.

Some of the earliest chromatic harps were fitted with a mechanical damper between the two rows of strings near the soundboard, and operated by a pedal. This was a brilliant innovation, but one soon abandoned.

The chromatic harp thus had three types of sound boxes.

The first, standard one was joined to the soundboard like a straight soundboard harp, which made it bulky. Another sound box extended the board, in the American style. Another, very beautiful solution was gently curved on each side, in a kind of synthesis between the straight and extended sound bodies.

The Harp-Lute.

In 1907, around serial no. 600, Pleyel also launched a variant of the chromatic harp: the harp lute. Specially designed for Baroque repertoire, this rare harp, often decorated, had entirely metal strings to evoke the timbre of the harpsichord.

It is curious to find the harp and the lute brought together in the Pleyel harp lute. The two instruments are so far apart both in terms of sound, and in how the instruments are built. Moreover, the harp lute, with its metal strings, had absolutely nothing in common with the lute.

It does not seem that Pleyel made any lutes, but some historical instruments were updated and modernised with little concern for authenticity. They were not copies of antique instruments, but modern variants, such as the harpsichord for which de Falla wrote his concerto.

The only thing the lute made at this time has in common with an original lute, is its back and the angle of the head. The very taut strings were not split; the frets were made of metal; and the pegs were replaced by guitar systems. This lute therefore only resembled a kind of large mandolin tuned like a guitar, whose shapes vaguely recalled the old one, and had nothing to do with today's reconstructions.

Postcard, photo of Charm (Pleyel Harp, metal neck)

Above all, the harp lute subscribed to the popular image of the lute at the beginning of the twentieth[1] century: sweet music, for tender romances and nocturnal serenades in the light of the summer moon. But the lute is also the instrument of laments and lamentations: an instrument of charm and seduction, but also sorrow and tears. It is the instrument of feelings. The lute, along with the lyre and the harp, is also part of poetic vocabulary: “every nerve, every fibre trembles like a freshly-tuned lute”, to quote Alfred de Musset as just one example.

The name “harp lute” also undoubtedly sounded more poetic, and certainly not as dry as “chromatic harp with metal strings”. It probably appealed more to the harpist - and to the potential buyer, to bring us all back down to earth. Pleyel did not hesitate to use this cliché to promote its harps, as this amusing postcard shows.

Erard had also used the same reference to the lute in 1889, for an instrument he had invented called the luteal [13], although the reference is closer to the "lute stop" of harpsichordists.

Pleyel, too, had harpsichordists more in mind than lutists. Thanks to its metal strings, the harp lute was proudly presented by Gustave Lyon as the ideal instrument for performing harpsichord repertoire:

There is nothing more delightfully beautiful, and more moving, than hearing these historical harpsichord pieces performed on the harp lute. It has even been called a revelation, because the subtle and expressive touch of the artist gives them appeal, a life, poetry, and emotion which they cannot have on a harpsichord.

Indeed, Saint-Saëns said: “On the harpsichord, it was impossible to move gradually from piano to forte. It is being able to practise the learned art of infinite nuances and variety of touch, which gives the modern piano its greatest appeal.”

Like the piano, the harp lute allows the learned art of infinite nuances. Thanks to it, Rameau, Handel and Bach have found an instrument that revives their souls, their joys, their sadnesses, their pains, with an intensity and a truth of expression unknown even while these great masters were alive. The harpsichord, for them, could only ever be a cold and inexpressive performer.

Warming to his theme, Gustave Lyon even implied that the sound of the harp lute would have been the one Bach had dreamed of for the harpsichord, and made a somewhat flamboyant comparison between the harpsichord’s plectrum, and the harpist's finger.

Indeed, the debate about performing early music on modern instruments is not new, and it is probably out of concern for authenticity that Gustave Lyon relied on the wishes expressed by Bach: “Bach wanted an instrument with plucked strings, but with a sustained, supple and flexible sound”.

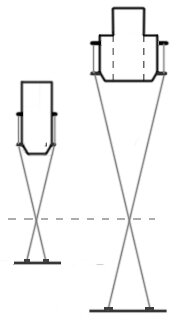

Initially, this harp-lute had two thin columns, which, arranged in an inverted V shape, ensured a very good balance for the harp. However, this model was not produced much, even if it received a very good press at the time - especially under the fingers of Renée Lénars, who specialised in playing it.

At least two models were made. One was in Gothic style, in walnut or mahogany, with an owl's head sculpted on the shoulder and a figure carved out of the head, like double basses had. The other, much more modern, is in the art nouveau style fashionable at the time, with typical, elegant curves along the two necks.

Harp-lute with two columns, Gothic walnut model.

Harp-lute, art nouveau style

Richard Wagner and the Chromatic Harp.

It has often been heard that Richard Wagner wrote his harp parts directly for Pleyel chromatic harp, which is what makes them so difficult on the pedal harp. Some passages, such as the last scene of Die Walküre for example, do have particularly difficult pedalling. However, the idea is still absurd, because Wagner died in 1883 - well before Gustave Lyon started making chromatic harps.

Harp-lute “Beckmesser” 136cm, 45 strings

On the other hand, for the Meistersinger von Nürnberg, Cosima Liszt (who had been conducting the Bayreuther Festspiele since the death of her husband Richard Wagner), had had a small harp lute accompany Beckmesser for her serenades, rather than a lute. While there is nothing terribly chromatic about Wagner's lute part, it is more the timbre of the harp lute itself that was exploited in Bayreuth. Its influence then extended to the opera houses of Paris, Mannheim, Amsterdam, The Hague, Venice, Milan, etc., where the lute was used for serenades.

Cosima wrote about this to Gustave Lyon on July 2, 1899 :

The lute [harp-luth] that you were so kind as to supply for the Bayreuth performances was produced in the presence of the three choirmasters and the harpists of our orchestra. We are unanimous about the beauty, advantage and merit of your invention.

This instrument, ravishing in form as well as in sound, will decorate our music hall, and I cannot tell you, Sir, how much I appreciate your kind attention.

Receive, Sir, with my thanks and those of my son, my highest esteemC. Wagner

Beckmesser's lute harp was a small chromatic one: 1m36 compared to 1m88. It had only 45 strings, compared to 78: 26 white and 19 black strings, i.e. a little less than 4 octaves.

If time ran out for Wagner before he could get to know the chromatic harp, some of his opera harp parts are sometimes played chromatically. The harp writing lends itself well to this: no (or very few) glissandos, chromatic modulations, chromatic foreign notes, etc.

Friend and great defender of Wagner's music, the great conductor Hans Richter, who was the first to conduct the entire Ring Cycle in Bayreuth in 1876, wrote to Gustave Lyon:

Bowdon (Cheshire) 14 janvier 1903

For a long time now, I have wanted to write to you about your excellent chromatic harps; my travels and professional obligations have prevented me from doing so until now.

With this instrument, there are no longer any obstacles now to the execution of even the most difficult parts of R. Wagner's masterpieces; I was able to convince myself of this when I conducted Götterdämmerung, in Paris. It was a great joy for me to hear the four female harpists playing on your instruments.

The main advantages of your instrument seem to me to be summed up as follows: firstly, the irreproachable sonority; secondly, the reliable tuning, because the strings are neither too taut nor too flaccid; thirdly, the complete absence of exterior noises during playing, because on pedal harps, the sound of the pedals being changed so rapidly is absolutely inevitable. I was completely satisfied with the sound of the chromatic harp.

In the hope that your improvement will soon be universally adopted, I remain your very friendly -Hans Richter

Other Chromatic Harp Makers.

Curiously enough, it was at exactly the same time that the British-born American harp maker Henry Greenway (1803-1903) also launched a chromatic cross-strung harp.

There are some troubling similarities with the Pleyel harp system, but it is very unlikely that Gustave Lyon could have copied this new instrument from so far away.

Accurately speaking, Greenway did not cross two rows of strings but rather almost two harps: two necks, and two X-shaped crossed columns are joined by one and the same sound body, for 43 white strings and 30 black strings from low F to high E.

These instruments are now extremely rare, but at least two are listed. One is in the National Music Museum in Vermillion, South Dakota, and the other in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. The arabesques on their soundboard bear witness to Greenway's English roots (he was born in Birmingham), and are reminiscent of the arabesques on some J. & J. Erat harps of the 1830s. In the same way, they are the same size of these English harps (at least in height!): 168cm, compared to 188cm for Pleyel.

On the first instrument, the soundboard is common to both harps. On the other hand, on the New York instrument, two inclined soundboards were placed side by side, thus considerably increasing the vibrating surface, and also making the structure much stronger.

Despite the apparent resemblance to Pleyel's chromatic harps in principle, a harpist would find it hard to switch from one to the other: the two rows of strings are reversed. The row of white strings on the Pleyel (playing naturals with the left hand close to the soundboard), is that of the sharps on the Greenway.

Henry Greenway - chromatic harp, circa 1895, single soundboard.

[National Music Museum]

Henry Greenway - chromatic harp, circa 1895, two isosceles soundboards.

[Metropolitan Museum of Art de New York]

Another chromatic harp with a completely different system was also patented in 1900, this time on the other side of the Rhine by Karl Weigel.

Karl Weige invented a simple system: a chromatic harp with a single row of strings. This very rare harp was made by the firm Julius Heinich Zimmermann in Saint Petersburg, probably around 1902.

This is a harp on which the chromatic total was arranged equally: the chromatic scale simply replaced the diatonic scale of a normal harp. The spaces between each string were completely even, not a diatonic scale with black keys added inside, as on a keyboard.

The strings were therefore of equal distance, whether they are naturals or sharps, but on the other hand, they were obviously much tighter than on a standard harp.

In reality, this 54-string instrument was very close to the Tyrolean harp, especially in the curvature of the sound body.

To better balance the weight distribution of the strings, they were fixed inside the neck, like the perpendicular harps of Dodd and Dizi - and as in traditional Paraguayan harps.

Unfortunately, this instrument did not enjoy much success, despite its strong potential.

More than a century later, the harp maker Philippe Volant proposed a chromatic lever harp according to the same system, with 61 strings in a single row.

harp system Karl Weigel, firma Jul. Heinz Zimmermann (Berlin,

4. Born in Namur, Dieudonné-Félix Godefroid (1818-1897), like his brother Jules, studied the single-action harp at the Paris Conservatory with Nadermann, before moving on to the double-action harp with Théodore Labarre. Godefroid then studied with Parish-Alvars, himself a pupil of Dizi.

5. Born in Liege, Alphonse Hasselmans (1845-1912) had a career path quite similar to that of his teacher Félix Godefroid. In 1884, he was appointed professor at the Paris Conservatoire, a position he held until his death in 1912. In addition to his compositions and many charming "character pieces", his teaching gave birth to a generation of virtuosos who made the French harp school world famous: Lily Laskine, Pierre Jamet, Micheline Kahn, Marcel Grandjany, Marcel Tournier, Carlos Salzedo, Henriette Renié, etc...

6. Henri Pape (1789-1875), piano maker, former director of the Pleyel workshops from 1811 to 1815, was a most inventive piano makers. He filed no less than 173 patents, including 73 for the piano! Among other ingenious innovations, he was the first, in 1826, to cover piano hammers with felt instead of the usual leather. He also filed a patent for cross strings as early as 1827, well before Steinway's patent of 1859. Henri Pape also conceived of many other innovations, such as the piano without strings, replaced by metal blades (which woukd later give rise to the celesta), the round piano, the piano-table, the hexagonal piano, the piano with two soundboards connected by a soundpost, the piano with strings on each side of the table, etc

7. The height of a sound was still measured in France in feet, as Heinrich Rudolf Hertz's system was not yet an international standard. Organ registrations have been using feet for a very long time: stops of 32, 16, 8 feet, etc. C 32 feet equals 16.5 Hz, and A 870 feet equals A 435 Hz.

8. Félix Godefroid, incidentally, died two years later in this holiday home.

9. Despite their greater strength, these necks sometimes broke in the same way as wooden ones. Given their weight, they caused more collateral damage to the soundboard when they did so.

10. An amusing testimony, which readily admits that the harp was an instrument mainly played by women. Gustave Lyon adds a little further on, in defence of his harps, that "the pedal-less chromatic harp rests on the knees and not on the chest, which, from the point of view of health and hygiene, especially when young girls are growing up, is of the utmost importance”.

11. Idem.

12. Founded in Chicago in 1864 by George Washburn LYON (no connection to Gustave Lyon) and Patrick J. HEALY, the firm Lyon & Healy launched its first harp, with a straight soundboard, in 1889, and the first extended soundboard harp in 1895. The firm Lyon & Healy, often compared to Steinway for the harp, is today the oldest firm still in business.

13. The luteal is a kind of grand piano whose particular mechanics produce a sound intermediate between piano and cymbalum. Ravel wrote Tzigane, in its initial version, for violin and luteal.

![Henry Greenway - chromatic harp, circa 1895, single soundboard. [National Music Museum]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5e5bd59984c054209746f363/1585238995282-V4NCTNR45BZ4ZVQNZSSM/Greenway+1.png)

![Henry Greenway - chromatic harp, circa 1895, two isosceles soundboards. [Metropolitan Museum of Art de New York]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5e5bd59984c054209746f363/1585239033425-MCX1O9JQ8AJT9CTH4SA9/image-asset.jpeg)